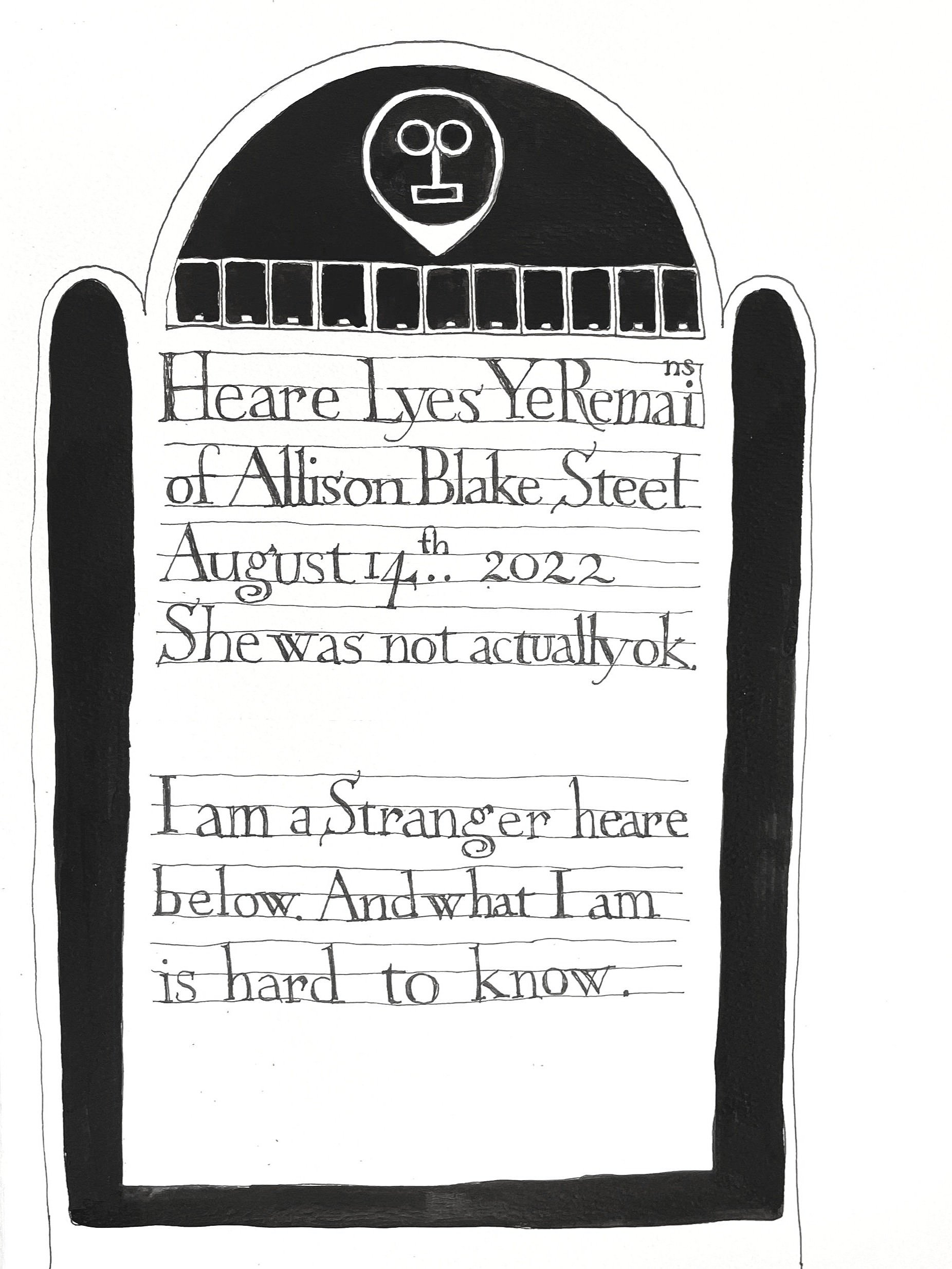

Elizabeth attended a local reading of the Declaration of Independence and approached Theodore Sedgwick a local lawyer to take her case, along with a fellow enslaved man known as Brom. The case was heard in the Great Barrington County Court in August 1781 and Sedgewick argued that the language of the constitution effectively abolished slavery in the state. “Bett and Brom” won their case and were granted their freedom. This ruling did not lead to the immediate emancipation of all slaves in Massachusetts (as I was taught in my youth.) But, of course, it was more complicated. The 1790 census in Massachusetts recorded no slaves, but it is believed that slave-owners were discouraged from mentioning slaves on the census. Glenn Knoblock writes: “While it is commonly and erroneously thought that the Walker and Mum Bett cases effectively ended slavery in Massachusetts (slaves were held in the state even after 1800), they were very important precedents in that slave owner’s claims could no longer be effectively argued or upheld in a court of law in Massachusetts.” -African American Historic Burial Grounds and Gravesites of New England G. Knoblock. After she gained her freedom Elizabeth took the name “Elizabeth Freeman” and went to work for the Sedgwick family, she also worked as a midwife delivering many local children in Stockbridge MA. Her gravestone is in Sedgewick's family plot in the cemetery in Stockbridge MA and was probably written and purchased by Catharine Sedgewick whom she helped raise and who recorded most of the known stories about Elizabeth’s life.